Trapped in the Middle: How Broken Systems Push Food-Insecure Families Toward Obesity

January 29, 2026

It might sound surprising, but individuals facing food insecurity are at increased risk of obesity. This is known as the obesity–food insecurity paradox—a complex cycle where limited access to healthy food leads to poor nutrition, driving the risk of chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and asthma.1,2

This paradox is deeply rooted in the social determinants of health: factors like household income, education, transportation, neighborhood conditions, and access to healthcare that influence how families live, work, and play. Families have limited control over many of these conditions, and the current food-relief system does little to address food insecurity holistically. The current social care ecosystem’s failure leaves families to make tradeoffs and puts children, who have the least agency within a household, at greater risk of diet-related diseases.

For many families, eating healthy isn’t about choice—it’s about access and affordability. Grocery stores may be miles away, while fast food is around the corner. Even when families want to purchase fresh, nutritious foods, the cost of produce compared to processed snacks often puts healthier options out of reach.

Federal safety net programs like SNAP and WIC are meant to fill these food insecurity gaps. However, food assistance typically targets immediate hunger needs and, on its own, doesn’t fully address whole-person health or close broader SDOH gaps that are often driven by non-food barriers like housing, transportation, benefits access, and utilities. Twenty-two percent of Full Cart applicants are enrolled in SNAP, yet these families still come to U.S. Hunger (more than 318,000 families since 2020) for additional support, seeking food assistance through the Full Cart program.

Food banks and supplemental programs offer essential relief, but they rarely address the underlying conditions driving food insecurity and the need for assistance. This is why so many families cycle in and out of the system: enrollment alone does not resolve the structural inequities that shape household food and nutrition access.

The result is a growing number of children facing both hunger and obesity—two challenges rooted in the same problem: broken, disconnected systems that provide temporary relief but not lasting support for families to thrive

The Cycle of Food Insecurity and Childhood Obesity

Obesity is often framed as a matter of personal choice (e.g., preference for nutrient-poor foods and inactivity), yet the reality is far more complex. Children’s health behaviors are shaped by the environment they are raised in—an environment that becomes increasingly restrictive when families face financial strain

Childhood obesity today affects nearly 20% of children in the U.S., up from just 5% in the 1970s—a fourfold increase over two generations.9 Children living in resource-strained households are disproportionately affected, putting them at a higher risk of developing chronic conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes) associated with obesity.

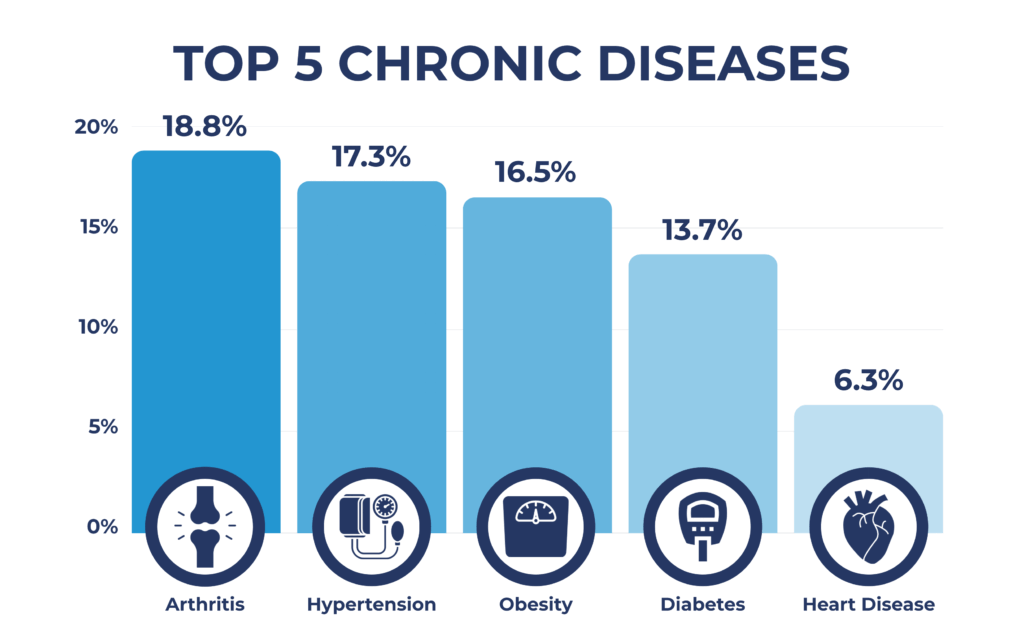

Among Full Cart applicants who have children, 53.6% reported chronic diseases, with the most common being arthritis (18.8%), hypertension (17.3%), obesity (16.5%), diabetes (13.7%), and heart disease (6.3%).

Neighborhoods with limited resources often lack grocery stores that offer quality produce, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products.⁵ Nearly 50% of Full Cart families lack access to reliable grocery transportation, limiting both choice and frequency of shopping trips. Even when healthy options are available, they are often unaffordable or perish too quickly. More than 63% of Full Cart families report being unable to afford balanced meals, forcing parents to choose low-cost, often calorie-dense and highly processed foods—products that increase the risk of childhood obesity.

Stacked Pressures: When Every Decision Has a Cost

These food system constraints overlap with broader financial challenges and priorities. Families must juggle limited resources between rent, utilities, transportation, childcare, and medical care. For example, among Full Cart families, 1 in 3 report daily food insecurity, 41% lack access to transportation for medical appointments, nearly half (48%) are at risk of having their utilities shut off, and 30% face unsafe or inadequate housing.

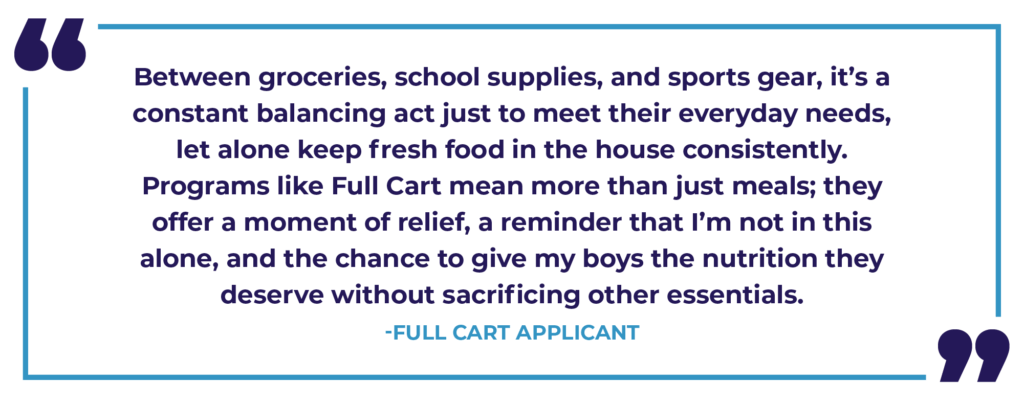

When tradeoffs become unavoidable, food is the most flexible—and therefore most often sacrificed—expense. As one Full Cart applicant explained, “It’s $5 for 4 lbs of chicken legs vs. $3 for cabbage. Which do you think will last and keep you full? Those are the constant choices I have to make. When the best option would be both with some grains to keep one balanced, full, and last longer.”

This is not a reflection of personal failure; it is evidence of families adapting to systems not designed with their realities in mind.

Increasing Food Access Alone Doesn’t Solve the Problem

Food distribution is a critical first step in meeting urgent needs, but lasting stability requires more than meals alone. However, real-time, household-level coordination and cross-sector collaboration are needed to address the underlying economic challenges families face. Current supports are helpful, but often they are not enough, as illustrated by another Full Cart applicant’s account: “While we do receive SNAP, it oftentimes isn’t enough to stretch the whole month. We have a hard time making ends meet, let alone buying groceries outside of the budget.”

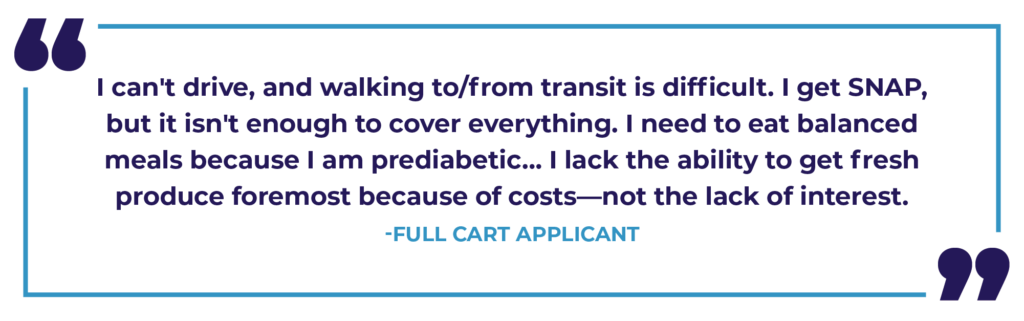

SNAP is the largest federal nutrition program, yet benefits average only $187 per person per month—an amount that does not align with rising food costs or the inflated price of produce.7 Many families rely on SNAP, but the program does not address key barriers, such as transportation, rising grocery prices, and the presence of food deserts. Importantly, it does not fully address the root causes of food insecurity. While SNAP supplements a portion of a family’s grocery budget, it falls short of creating lasting economic stability. A single mom and SNAP recipient shares,

Full Cart families show this firsthand; despite receiving assistance, many still experience daily or weekly food insecurity, nutritional insecurity, and chronic financial strain.

Breaking the Cycle, Not Just Easing the Symptoms

The link between hunger and obesity reveals a critical truth: solving food insecurity isn’t about providing more food; it’s about providing better food and addressing the broader conditions shaping a family’s health.

U.S. Hunger’s model demonstrates that part of the solution lies in listening to families, identifying barriers in their daily lives, and tailoring support to meet real needs. Full Cart fills gaps by serving households that don’t qualify for benefits or struggle to make ends meet with the benefits they do have. The program provides additional grocery support, reaching rural and food desert communities, providing emergency and interim food assistance, and offering low-burden, home-delivery solutions to food-insecure families. Although the applicant’s journey involves food relief, it begins with a conversation. Program registration doubles as a Health-Related Social Needs screening, assessing families for unmet social care and health needs, including gaps in transportation, housing, and financial resources, as well as asking them how Full Cart can help. Applicant responses provide direct insight into the lived experience of food insecurity, enriching and evolving the traditional hunger conversation.

These firsthand accounts and testimonials reveal that food insecurity is the symptom of problems that extend beyond food access. It is the result of a culmination of factors that include income/affordability, transportation access, and more. These factors are also linked to nutritional insecurity and the obesity epidemic that is spreading among children. Food insecurity and obesity are symptoms of systems that fail families long before they enter a food pantry or submit a Full Cart application.

Programs like SNAP and WIC play an essential role, but they alone cannot shield families from the social and environmental forces that drive diet-related disease. To break the cycle, we must shift from a food-relief model to a systems-support model—one that recognizes food alone is not enough, transportation matters, housing matters, medical access matters, and income stability matters.

Community-based programs, like Full Cart, are becoming increasingly vital. They approach food insecurity with a focus that extends beyond food access. Using a data-driven approach, Full Cart informs the coordination needed for stability, partnership, and responsive support that meets families where they are.

If we want to reduce food insecurity and prevent childhood obesity long-term, we must build systems that provide the right support, at the right time, in the right way—interoperable systems that enable families not just to survive, but to thrive.

Sources

1. Shovels A. Understanding the paradox of obesity and food insecurity. Updated December 22, 2023. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/understanding-the-paradox-of-obesity-and-food-insecurity

2. The role of the federal child nutrition programs in improving health and well-being. Food Research & Action Center. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-health-role-federal-child-nutrition-programs-improving-health-well-being.pdf

3. Mostafavi B. Children with chronic conditions may face higher risk of food insecurity. Updated September 26, 2025. https://www.michiganmedicine.org/health-lab/children-chronic-conditions-may-face-higher-risk-food-insecurity

4. How is food access related to chronic disease. Updated October 22, 2024. https://www.ifm.org/articles/food-insecurity-chronic-disease

5. Understanding the connections: food insecurity and obesity. Updated October 2015. https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/frac_brief_understanding_the_connections.pdf

6. Gutierrez E. Changes to SNAP and Medicaid Would Have Implications for Student Access to School Meals. The Urban Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED673533.pdf

7. Coulson M. What Is SNAP? And Why Does It Matter? Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/what-is-snap-and-why-does-it-matter

8. Why SNAP Matters and How We Can Help. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://americanhealth.jhu.edu/news/why-snap-matters-and-how-we-can-help

9. Cheryl Fryar MC, Joseph Afful. Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Severe Obesity Among Children and Adolescents Aged 2-19 Years. Centers for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity-child-17-18/obesity-child.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com