It’s Not Just Hunger: Transportation’s Role In Food Insecurity

August 29, 2022

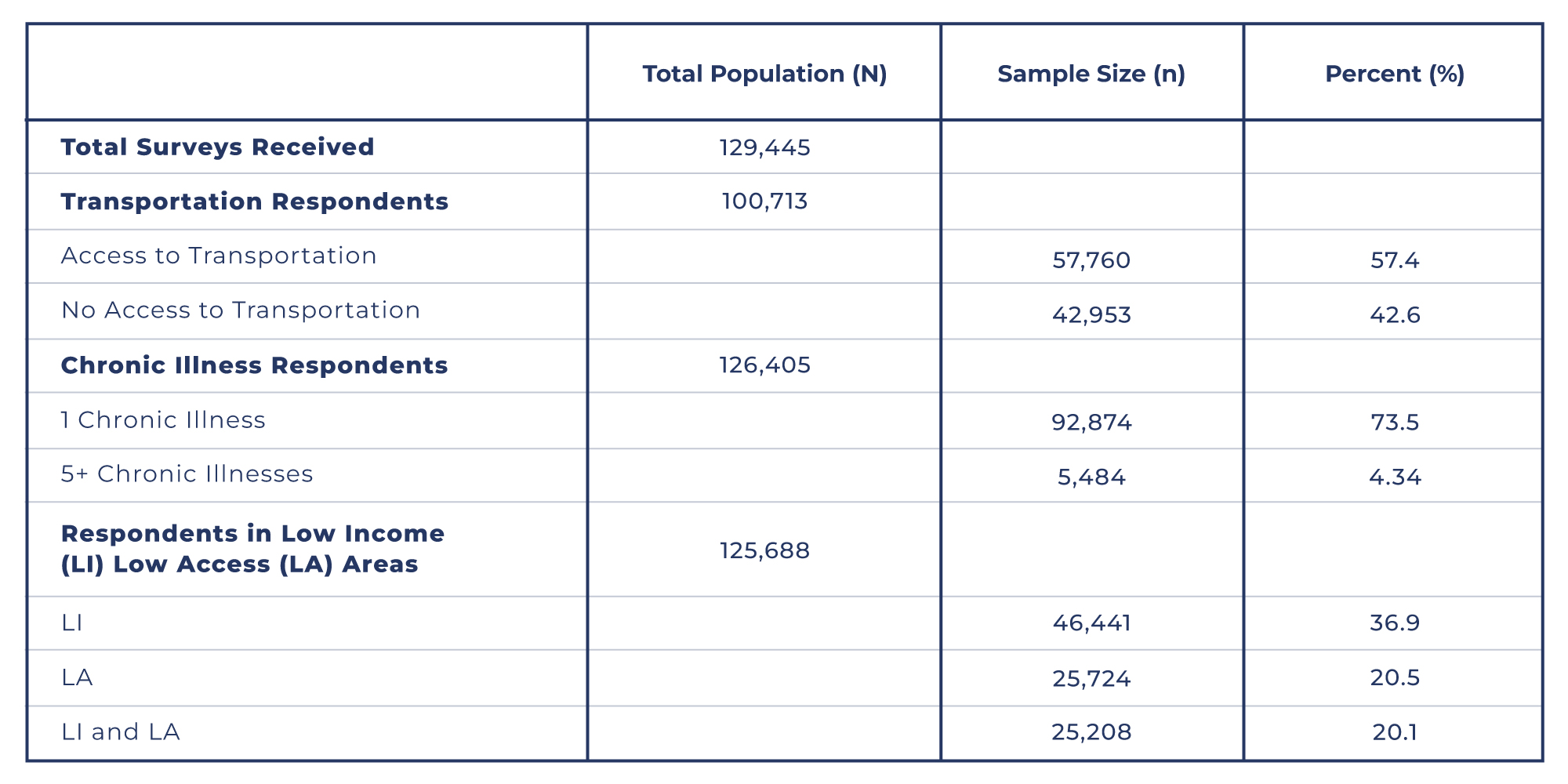

Ahead of the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health slated for September 2022, the Biden-Harris administration has announced that one of their main focuses will be improving access and affordability of food. Particularly, one aspect of their initiative will involve improving transportation to make food more accessible to Americans.1 Since 2020, U.S. Hunger has collected over 129,445 food insecurity surveys from individuals who have requested food assistance due to financial uncertainty or an inability to find sufficient food in their area (see Table 1). Within a subset of the surveys collected, 42.6% of individuals reported that they do not have access to transportation to go to grocery stores that provide fresh and healthy food options. In their responses to how a home delivery of a box of farm-fresh or non-perishable foods (i.e., a Full Cart® box) could help them, 648 people specifically listed a lack of “transport” or “transportation” as a reason for not having the food they need. One person explained, “Sometimes we have no money or food to eat and I don’t have transportation to get free food donations and would like to get food donations delivered to my home, so at least the kids have something to eat.” This personal account is just one illustration of the significant role transportation serves in making food accessible to families across the nation. Not only are individuals having difficulty procuring transportation to grocery stores, but they are also unable to access the free food donations offered by local food pantries and other no-cost providers due to long distances and a lack of transit services.2 As a result, many economically disadvantaged Americans are more likely to rely on their social networks for rides, or they may be faced with the decision to go without food if they are unable to allocate their limited income towards transportation services like Uber or local bus services, to the nearest grocery store.3

In conjunction with transportation difficulties, many Americans are also coping with chronic illnesses, putting them at an even greater risk of facing food insecurity. Of those who applied for food assistance through U.S. Hunger, a majority (73.5%) reported that they or a member in their household are managing at least one chronic illness (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease) with 4.34% of respondents listing five or more illnesses. One recipient of a Full Cart box reported, “Food on the table was like reaching for stars. Many times there wasn’t anything to eat. Congestive heart failure won’t allow me to walk and get the things I need.” While another recipient explained, “I have had a hard time finding transportation to the store. I’m handicap and in a wheelchair so [it’s] hard to get around.” These firsthand accounts demonstrate the hardship that can oftentimes be the product of poor health and disability. In an effort to prevent further complications from their chronic illnesses, individuals diagnosed with one or more chronic illnesses are commonly encouraged by their medical providers to eat more nutritious foods. However, the same financial constraints that make transportation inaccessible, also result in nutritious foods being unaffordable, putting low-income individuals with chronic diseases at a heightened risk for further health challenges.2,4 Even if they are able to acquire food, individuals faced with income and transportation challenges are more likely to buy the more affordable, poorer quality foods that are available at the corner stores (e.g., convenience stores, gas stations) located closer to home.2,5 Furthermore, older adults (ages 55 and older) who are reliant on medication to treat or reduce the symptoms of their illness have been found to prioritize food over the medication they need, resulting in low medication adherence that could lead to further health complications.6,7 Thus, in many ways, food insecurity is compounded by the constraints that limited transportation and health issues pose to individuals who are already facing economic hardship.

An inability to acquire healthy and nutritious food, therefore, indicates that poorer health outcomes are on the horizon for individuals living across the nation and underscores the need for effective food assistance. Since 2020, U.S. Hunger has received requests for food assistance from over 25,724 individuals living in food deserts (i.e., the nearest supermarket is more than 1 mile away in urban areas or more than 10 miles in rural areas). For households located in such low-access regions, hunger is often the result of a lack of proximity to a food store, which may be additionally exacerbated by a lack of financial resources as well. In addition to low access, many individuals also experience low income. For example, 46,441 individuals lived at or below the poverty line at the time of applying for food assistance with 20.1% of families experiencing both low income and low access to healthy food. The ability to acquire food for many Americans, therefore, becomes not only an issue of proximity to a food provider, but also one of socioeconomic origin. Physical limitations and chronic illness make it difficult for individuals without transportation to walk to the nearest grocery store for food, but walking is the only option for some, especially those burdened financially. One solution to make healthy food more attainable for everyone is to increase the availability and reach of affordable, public transportation in both urban and rural regions. Increasing the overall availability of public and demand-responsive transit, while also ensuring that those services are provided along routes of food retailers, farmers’ markets, and other nutritious food providers, would greatly improve food accessibility and health. In previous studies, accessible and affordable transportation has been associated with increased physical activity and reduced rates of obesity.3,8 Subsequently, though transportation represents a small contributor to food insecurity, it has the potential to play a major role in reducing health disparities in more than one way. Expanding transportation routes to food providers would certainly benefit many around the nation and should be a priority for the White House administration moving forward in their agenda on ending hunger; however, additional solutions to food accessibility shortcomings also remain. For instance, at U.S. Hunger, we have taken another approach to food accessibility by eliminating the client’s dependency on transportation altogether. Through our Full Cart®, we have established a virtual food assistance program that provides nutritious foods to individuals in need by delivering them directly to their front door. For families without access to transportation, this service removes several challenges to acquiring nutritious food. They no longer need to allocate funds towards transit options, depend on social networks, or have to consider the time spent traveling to distant food providers. By providing this food delivery service U.S. Hunger can provide food assistance to Americans across the nation in a discrete and dignified manner. This option eliminates individual-level dependency on transportation while also having the potential to be of benefit to others on a macro level. In previous studies, the direct delivery model for food assistance has been shown to reduce healthcare expenditure and utilization.9,10 Food and meal delivery programs consequently have the potential to eliminate food accessibility barriers for vulnerable populations while economically benefiting all Americans. Thus, in addition to improving transportation services, the White House should also consider food assistance delivery options and programs.

• • •

Subscribe to our Data & Research Newsletter Here.

U.S. Hunger (USH) is a non-partisan, not-for-profit established in 2010, which has mobilized more than 850,000 volunteers to distribute over 147 million nutritional meals as of July 2022. Utilizing real-time data analytics and technology to operate a national home delivery service for the food insecure, USH uses a SaaS-based data tool to gain comprehensive insight into what factors lead individuals to seek food assistance. We work alongside corporate and community partners to identify and provide food assistance to those in need through our Full Cart® program. For more information contact data@ushunger.org.

Table 1. The total population size (N), sample population size (n), and their corresponding percentages based on responses to various survey questions.

References

1. White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health: Toolkit for Partner-Led Convenings. 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2022-06/White%20House%20Tookit%20%282%29.pdf

2. Shieh JA, Leddy AM, Whittle HJ, et al. Perceived Neighborhood-Level Drivers of Food Insecurity Among Aging Women in the United States: A Qualitative Study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 05 2021;121(5):844-853. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2020.12.019

3. Dumas BL, Harris DM, McMahon JM, et al. Prevalence of Municipal-Level Policies Dedicated to Transportation That Consider Food Access. Prev Chronic Dis. 11 18 2021;18:E97. doi:10.5888/pcd18.210193

4. Decker D, Flynn M. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease: Addressing Food Access as a Healthcare Issue. R I Med J (2013). 05 01 2018;101(4):28-30.

5. Wetherill MS, Williams MB, White KC, Seligman HK. Characteristics of Households of People With Diabetes Accessing US Food Pantries: Implications for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support. Diabetes Educ. 08 2019;45(4):397-407. doi:10.1177/0145721719857547

6. Jih J, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Seligman HK, Boscardin WJ, Nguyen TT, Ritchie CS. Chronic disease burden predicts food insecurity among older adults. Public Health Nutr. 06 2018;21(9):1737-1742. doi:10.1017/S1368980017004062

7. Nguyen NH, Khera R, Ohno-Machado L, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Prevalence and Effects of Food Insecurity and Social Support on Financial Toxicity in and Healthcare Use by Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2021;19(7):1377-1386.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.056

8. She Z, King DM, Jacobson SH. Analyzing the impact of public transit usage on obesity. Prev Med. Jun 2017;99:264-268. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.010

9. Berkowitz SA, Terranova J, Hill C, et al. Meal Delivery Programs Reduce The Use Of Costly Health Care In Dually Eligible Medicare And Medicaid Beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 04 2018;37(4):535-542. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.099910. Gurvey J, Rand K, Daugherty S, Dinger C, Schmeling J, Laverty N. Examining health care costs among MANNA clients and a comparison group. J Prim Care Community Health. Oct 2013;4(4):311-7. doi:10.1177/2150131913490737